Don't miss the next drop

American watch manufacturing once dominated global timekeeping, pioneering mass production techniques that revolutionized industry worldwide. From humble beginnings in 1850 Massachusetts to supplying millions of railroad workers and soldiers, American watchmakers like Waltham, Elgin, and Hamilton built an empire on precision, innovation, and reliability. Yet by 1970, this mighty industry had virtually disappeared, unable to survive competition from Swiss luxury brands and Japanese quartz technology. Today, a small but passionate revival keeps American watchmaking traditions alive through boutique manufacturers crafting timepieces in Detroit, Pennsylvania, and Nashville.

The story of the American watch industry spans 170 years of triumph, innovation, and ultimate decline. This is a cautionary tale about technological disruption and global competition that left behind some of the finest mechanical timepieces ever created.

Revolutionary beginnings: the birth of mass production

The American watch industry began not with craftsmen, but with visionaries who reimagined manufacturing itself. In 1850, Aaron Lufkin Dennison, David Davis, and Edward Howard founded what would become the Waltham Watch Company in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Dennison’s inspiration came from visiting the United States Armory at Springfield, where rifles were made with interchangeable parts, a revolutionary concept he believed could transform watchmaking.

The American System of Watch Manufacturing changed everything. Unlike Swiss watchmakers who relied on distributed networks of skilled craftsmen hand-fitting components, Waltham built massive integrated factories where specialized machines produced parts to thousandths-of-an-inch tolerances. Every component was perfectly interchangeable, assembled by semi-skilled workers rather than master watchmakers. The 1857 Waltham Model became the first practical American watch with truly interchangeable parts, selling for just $12 compared to expensive European imports.

This innovation sparked an industry explosion. The Elgin National Watch Company followed in 1864, building what became the world’s largest watch factory in Elgin, Illinois. By April 1867, Elgin delivered its first movement (the B.W. Raymond serial number 101) originally sold for $115 (equivalent to roughly $2,400 today). Together, Waltham and Elgin would eventually produce nearly 80% of all jeweled pocket watches made in America, accounting for approximately 95 million timepieces between them.

The Hamilton Watch Company emerged in 1892 from the bankruptcy of Keystone Standard Watch Company in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Hamilton would become known for producing “the finest American watch made,” earning distinction as “The Railroad Timekeeper of America.” Illinois Watch Company, Hampden, and dozens of other manufacturers joined the boom, making the late 19th century the golden age of American watch production.

American watch examples from the shop

1950’s Hamilton Automatic 10k RGP Case With White Dial

Railroad watches: when seconds meant lives

Nothing shaped American watchmaking more profoundly than the railroad industry’s demands for absolute precision. On April 18, 1891, near Kipton, Ohio, two trains collided head-on at full speed, killing nine people. Investigation revealed that an engineer’s watch had stopped for four minutes before restarting, creating a fatal miscalculation about the approaching train’s position.

The disaster prompted the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad to appoint Webster Clay Ball as Chief Time Inspector on July 19, 1891. Ball established rigorous standards that transformed American watch quality: minimum 17 jewels, lever-set mechanisms (preventing accidental time changes), adjustment to five positions and temperature extremes, and accuracy within 30 seconds per week. Crucially, Ball required biweekly inspections by certified watchmakers.

The 1893 General Railroad Timepiece Standards became industry law. Every railroad watch needed open-face cases, bold black Arabic numerals on white dials, winding stems at 12 o’clock, double roller escapements, and steel escape wheels. These specifications weren’t optional—they were life-and-death requirements. By 1908, Ball’s network included 2,000 authorized inspectors checking over one million watches across 180 railroads.

Hamilton’s Grade 992 became the most popular railroad watch ever produced, with over 600,000 made between 1903-1940. Waltham’s Vanguard and Crescent Street models, Elgin’s B.W. Raymond and Veritas movements, and Illinois’s Bunn Special and Sangamo Special represented the pinnacle of American watch precision. These weren’t mere timekeepers—they were precision instruments adjusted to withstand temperature extremes, position changes, and the constant vibration of locomotive cabs while maintaining chronometer-grade accuracy.

The railroad watch era established American manufacturers as world leaders in precision timekeeping, forcing even Swiss competitors to adopt American manufacturing methods. The phrase “on the ball” allegedly derives from Webb C. Ball’s reputation for accuracy, and modern Swiss COSC chronometer standards still reference Ball’s pioneering specifications.

The golden age: innovation and excellence

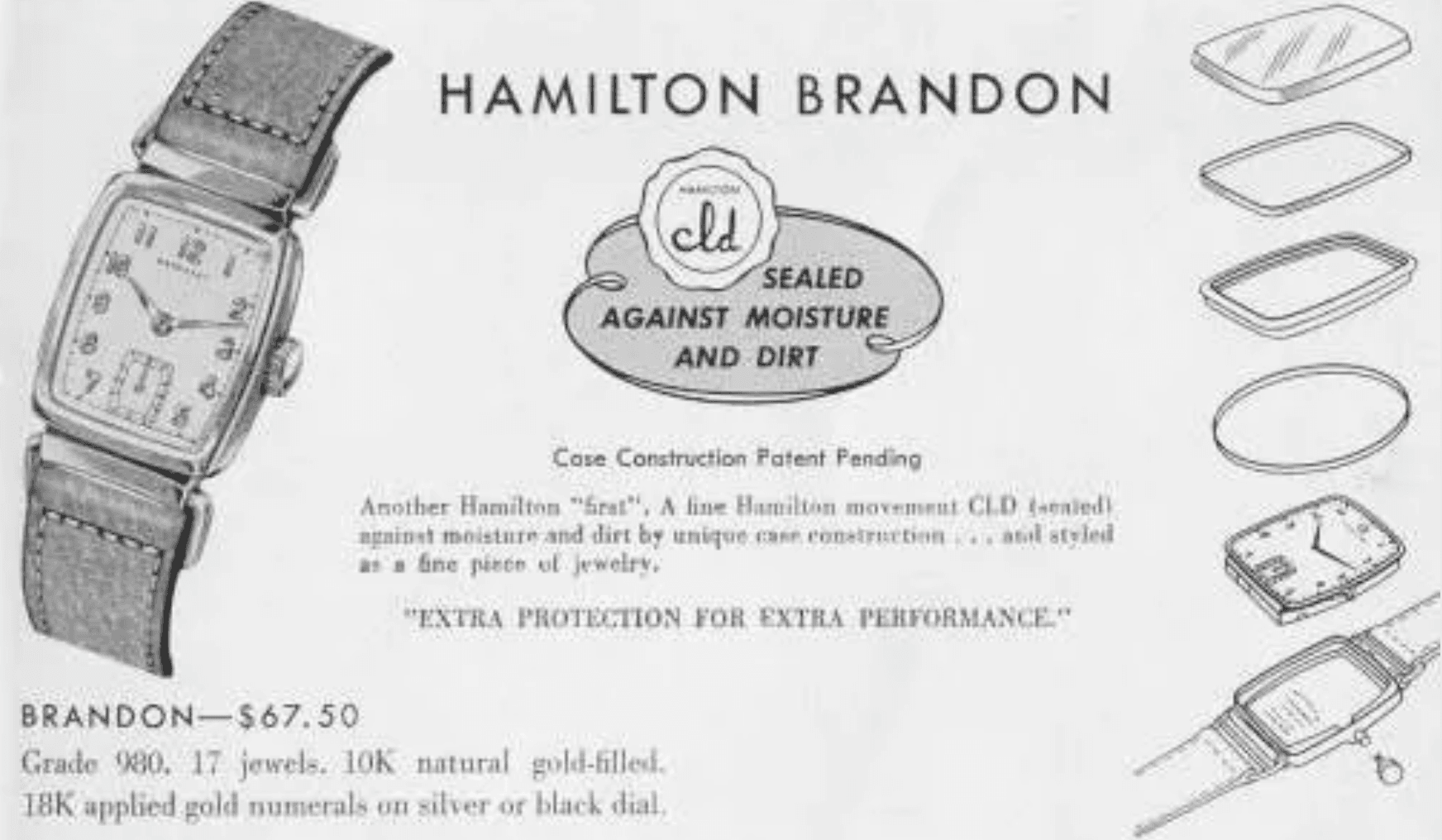

The early 20th century saw American watchmaking reach its creative and technical zenith. The transition from pocket watches to wristwatches began during World War I, when Hamilton introduced its first wristwatch in 1917 for men entering military service. Waltham created the world’s first waterproof wristwatch, the Depollier trench watch, in 1918, featuring protective grills and a revolutionary sealed case.

The Art Deco era of the 1920s and 1930s brought extraordinary design innovation to the American watch. Rectangular, square, and tonneau-shaped cases replaced traditional round forms. Geometric patterns, enamel inlays, and intricate guilloché work adorned dials and cases. Bulova produced over 350 different ladies’ Art Deco models between 1922-1930 alone, with names like Breton, Cambridge, Banker, and Commodore. Hamilton’s elegant models—Piping Rock, Meadowbrook, and Flintridge—were named after famous golf resorts and featured platinum cases with enamel bezels, selling for astronomical prices during the Depression.

Gruen’s Curvex, introduced in 1935, represented the ultimate expression of American watch design. This curved rectangular watch featured a patented curved movement (Caliber 311) that conformed to the wrist. It became an instant sales success, copied by virtually every watchmaker but never truly duplicated. Even Rolex used Gruen’s Caliber 877 movement in their Prince models.

World War II proved American manufacturing superiority. Hamilton ceased all consumer production in 1942 to concentrate on military contracts, successfully mass-producing marine chronometers for US Navy navigation—the first American-made chronometers. The company earned five Army-Navy ‘E’ Awards for excellence. Over one million American military watches were produced between 1942-1945, with the iconic A-11 specification watch becoming known as “the watch that won the war.” Manufactured by Elgin, Waltham, and Bulova with 15-17 jewel movements, hacking functions for synchronization, and luminous dials, these 32mm timepieces coordinated Allied operations including the D-Day landings.

Bulova’s revolutionary Accutron

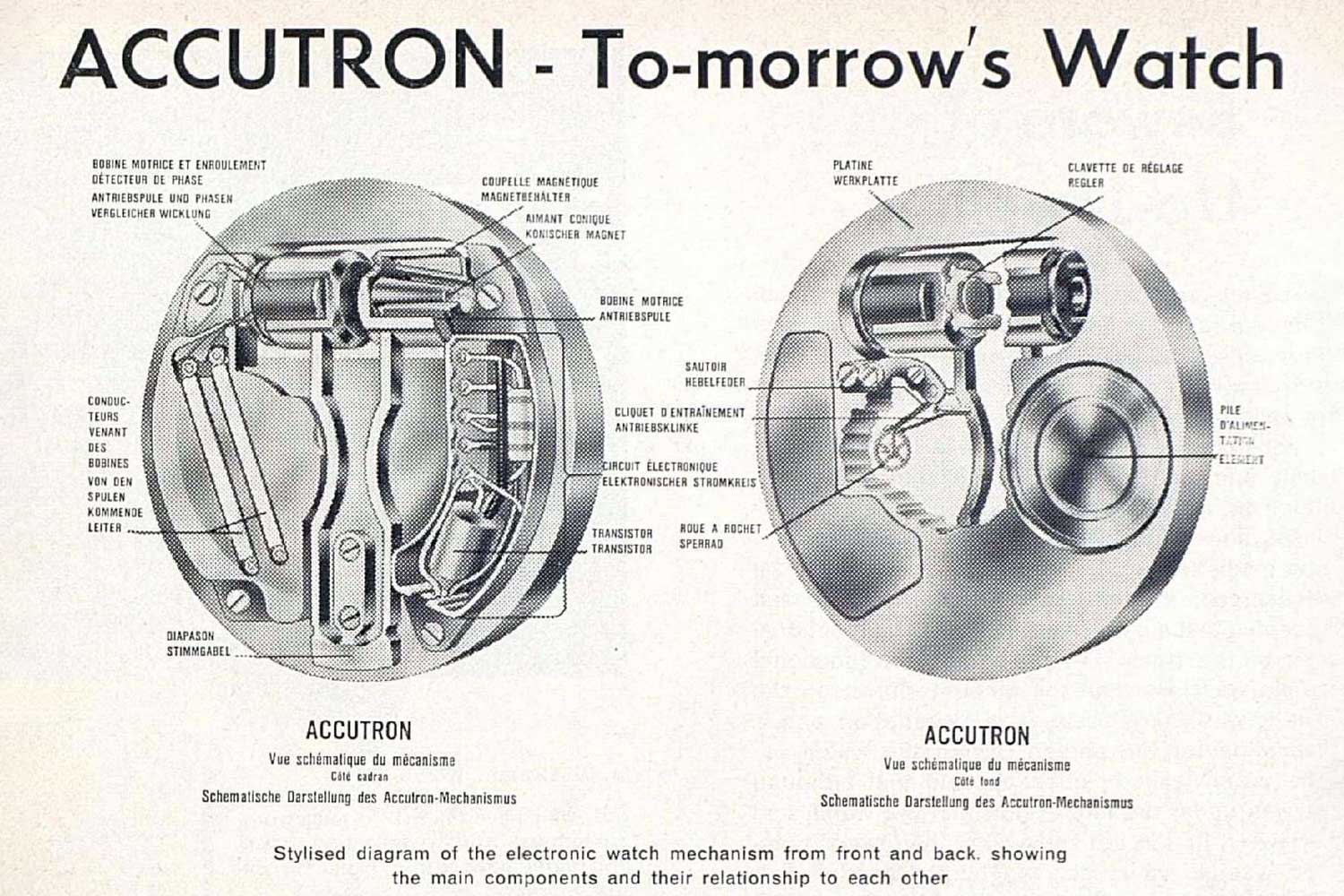

The most significant innovation in 20th-century American watchmaking came from Bulova in 1960. After ten years of development by Swiss engineer Max Hetzel and American engineer William O. Bennett, Bulova introduced the Accutron. The world’s first electronic watch powered by a 360 Hz tuning fork instead of a traditional balance wheel.

The Accutron achieved unprecedented accuracy of ±1 minute per month, making mechanical watches seem antiquated overnight. Its distinctive hum (the tuning fork was audible) and revolutionary technology captivated consumers and NASA alike. Accutron movements were used in 46 US space missions, from Explorer VI to the Apollo program. One Accutron movement remains on the Moon’s surface in the Sea of Tranquility. The Spaceview model, with its exposed tuning fork movement visible through a transparent dial, became the most collectible American watch of its era.

Hamilton countered with the Electric 500 in January 1957, the world’s first battery-powered wristwatch, eliminating the mainspring entirely. The famous asymmetrical Hamilton Ventura, designed by Richard Arbib in 1957, showcased this revolutionary electric movement in a Space Age shield-shaped case. Elvis Presley made it iconic by wearing it in “Blue Hawaii” (1961), earning the Ventura the nickname “the Elvis watch.”

By 1970, Hamilton introduced the Pulsar, the world’s first LED digital watch, priced at $2,100 (more than a car). American innovation led the electronic watch revolution, demonstrating that American manufacturers could pioneer new technologies while Swiss makers remained focused on traditional mechanical movements.

The catastrophic decline

The triumph proved short-lived. What began as American technological leadership in electronic watches became an existential crisis by the late 1970s. The problem wasn’t quartz technology itself, Hamilton and Bulova had pioneered electronic watches, but rather the complete inability to compete with Asian mass production.

Seiko’s Astron quartz watch launched December 25, 1969, followed by aggressive cost reduction that made quartz watches affordable. Within a decade, Japanese manufacturers (Seiko, Citizen, Casio) and Hong Kong producers flooded markets with watches that were more accurate, cheaper, and required less maintenance than any mechanical watch could match. By 1977, Seiko had become the world’s largest watch company with $700 million in revenue on 18 million units.

American companies couldn’t compete on price, couldn’t match Asian quality control and automation, and couldn’t pivot to luxury positioning like the Swiss. The Waltham Watch Company closed in 1957 after producing 40 million watches. The Elgin National Watch Company shut its Illinois factory in 1964 (demolished 1966) and ceased all US production in 1968 after making 60 million watches. The Hamilton Watch Company ended Lancaster production in 1969, moving entirely to Switzerland before being sold to SSIH (later Swatch Group) in 1974.

The Swiss survived through government-backed consolidation (forming ASUAG/SSIH, later The Swatch Group) and brilliant repositioning of mechanical watches as luxury goods valued for craftsmanship rather than timekeeping accuracy. American manufacturers stuck in the middle market had neither cost advantages nor prestige, and fragmented ownership prevented industry-wide coordination.

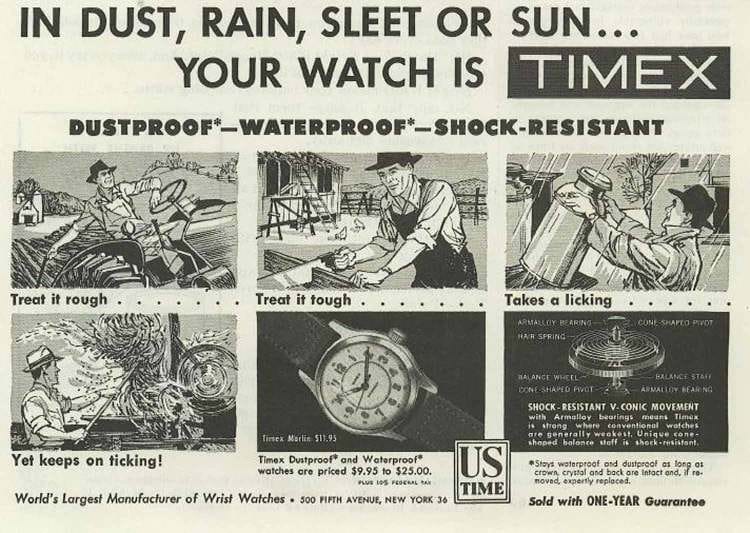

Only Timex Corporation survived by abandoning domestic manufacturing. Founded from Ingersoll’s dollar watch business in the 1940s, Timex pioneered inexpensive watches with proprietary Armalloy bearings instead of jewels. Their legendary “Takes a licking and keeps on ticking” advertising campaign (1956-1977) featured torture tests that made Timex synonymous with durability. By quickly moving production to the Philippines, India, and China, Timex captured the affordable watch market while every traditional American manufacturer disappeared.

The modern American watch revival

Since 2011, a small but passionate revival has emerged, focused on artisanal production rather than mass manufacturing. Shinola, founded in Detroit in 2011 by Tom Kartsotis, became the most visible American watch brand, growing from 9 to over 400 employees by 2021. While controversial for assembling watches from Swiss movements and imported parts (the FTC required them to change marketing from “Made in USA” to “Built in Detroit”), Shinola successfully returned watch manufacturing jobs to America.

The true standard-bearers are independent watchmakers creating genuine American timepieces. RGM Watch Companyin Pennsylvania, founded in 1992 by former Hamilton developer Roland G. Murphy, produces 90% US-made watches with in-house movements including the Caliber 801 (2008 – the first high-grade mechanical movement made in America in over 40 years) and the Pennsylvania Tourbillon (2010). Weiss Watch Company, founded by WOSTEP-trained Cameron Weiss, machines cases, crowns, and buckles in Nashville from stainless steel blocks and produces the Caliber 1003 movement that’s 95% American-made. J.N. Shapiro creates ultra-luxury watches ($70,000+) with intricate guilloché dials and fully in-house movements from a Los Angeles workshop.

These manufacturers represent American watchmaking’s future: small-batch, high-end production emphasizing domestic craftsmanship. Annual production measures in hundreds rather than millions, but the quality rivals anything from Switzerland. Vintage American watch collecting has exploded, with railroad-grade pocket watches and military timepieces commanding premium prices. The legacy of American innovation: interchangeable parts, hacking movements, the tuning fork Accutron, LED digital watches, continues influencing global horology even as domestic production remains minimal.

Conclusion: a legacy preserved

The American watch industry’s rise from 1850 to 1970 and subsequent collapse represents one of manufacturing history’s most dramatic stories. Companies like Waltham, Elgin, Hamilton, and Bulova didn’t just make watches they revolutionized industrial production, saved lives through railroad timekeeping standards, supported military operations across two world wars, and pioneered electronic timekeeping that eventually destroyed them.

Today’s collectors treasure American watches not merely as timepieces but as artifacts of manufacturing excellence. A Hamilton 992B railroad watch or Bulova Accutron Spaceview represents American ingenuity at its finest, precision instruments built when “Made in USA” meant the world’s best. While the days of American mass-produced watches won’t return, the revival of artisanal watchmaking by companies like RGM and Weiss ensures that American horological traditions survive. The story of American watchmaking reminds us that even the mightiest industries can fall, but the innovations and craftsmanship they created endure forever in the collectors and enthusiasts who preserve their legacy.

Related posts

The Rise and Fall of American Watchmaking: A Complete History

American watch manufacturing once dominated global timekeeping, pioneering mass production techniques that revolutionized industry worl...

The Evolution of the Rolex Datejust: 1945-1990

The Rolex Datejust revolutionized wristwatches in 1945 as the world's first self-winding waterproof chronometer with an automatically c...

The Ultimate Guide to Vintage Omega Seamasters

Vintage Omega Seamasters represent one of the most compelling propositions in watch collecting today - offering military provenanc...

The Expert’s Guide to Rolex Serial Numbers and Reference Numbers

Understanding Rolex serial numbers is essential for any Rolex enthusiast, collector, or potential buyer. These unique identif...

The Collector’s Guide to Vintage Wittnauer Chronographs

Vintage Wittnauer chronographs represent one of the most compelling value propositions in the world of mid-century timepieces. While br...

Wittnauer Pert-o-Graph Ref. 7005: An Analog Computer for the Project Manager’s Wrist

Wittnauer Pert-o-graph, tool watch or something else? In the history of horology, the "tool watch" has traditionally been defined by it...

The Expert’s Guide to Buying Vintage Watches on eBay In 2025

eBay, to the aspiring watch collector, is a landscape of profound contradiction. It is a digital bazaar of immense scale, a place where...

Complete Guide to the Rolex Datejust 1601

In the grand pantheon of horology, few timepieces command the same blend of understated elegance, historical significance, and everyday...

How the Quartz Crisis Nearly Ended Swiss Watchmaking

Before the quartz crisis (1970s), the Swiss watchmaking industry stood as an unshakeable colossus, a global symbol of precision, intric...

An Expert’s Guide to Omega Reference Numbers

Omega's rich horological history, stretching back to 1848, has produced an astonishingly diverse and extensive catalogue of timepieces....

Patina vs. Damage on a Watch Dial

Among vintage watch enthusiasts and collectors, one of the most debated topics revolves around patina and damage. What sets the two apa...

How Old Is My Bulova Watch? Production Date Guide

Bulova, one of the first companies to mass-produce wristwatches in the early 20th century, has made it easier than most to identify the...